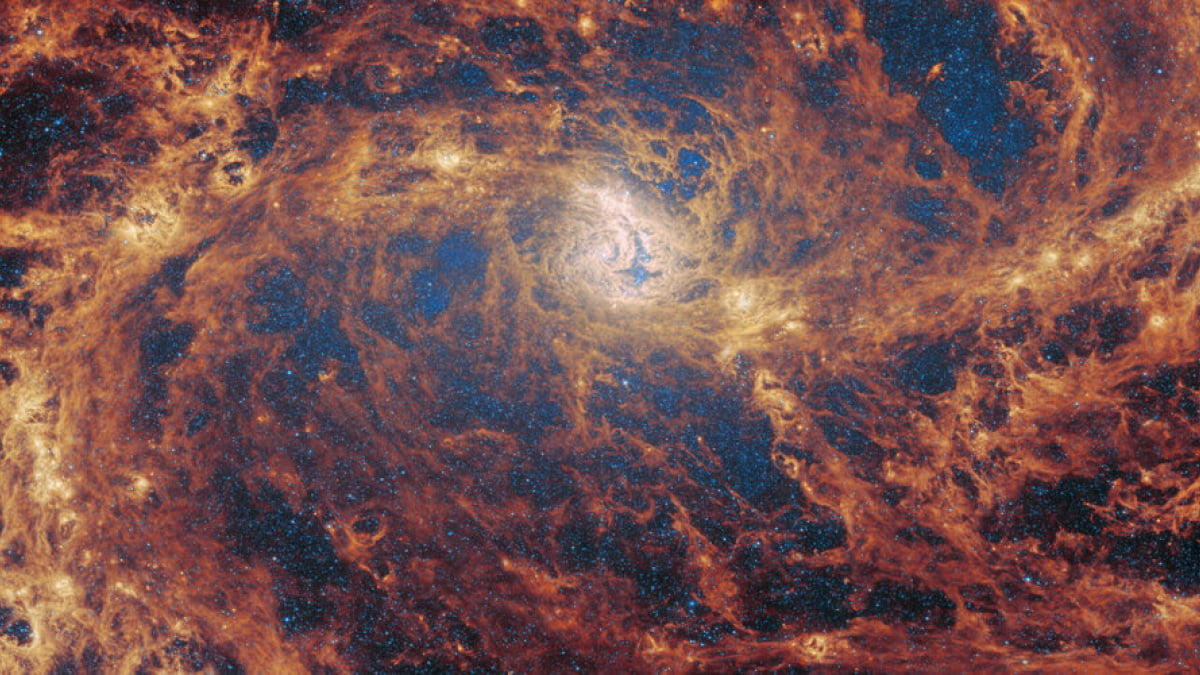

Scientists have found an unusual neon glow near the center of the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy for the first time.

This gas needs an enormous amount of energy to shine — more than normal stars can supply. The discovery, based on data from NASA‘s James Webb Space Telescope, likely means the barred spiral galaxy, sometimes called Messier 83 or M83, has been harboring an active, supermassive black hole in secret.

The new research, published in The Astrophysical Journal, upends prior thinking about the galaxy. Previously, it was assumed that if there were a hole in its heart, it would be dormant and certainly not shooting out high-energy radiation.

“Before Webb, we simply did not have the tools to detect such faint and highly ionized gas signatures in M83’s nucleus,” said Svea Hernandez, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, in a statement. “We are finally able to explore these hidden depths of the galaxy and uncover what was once invisible.”

These scientists think alien life best explains what Webb just found

Dust and gas obscure the view to extremely distant and inherently dim light sources, but infrared waves can pierce through the clouds.

Credit: NASA GSFC / CIL / Adriana Manrique Gutierrez illustration

Black holes are some of the most inscrutable phenomena in outer space. About 50 years ago, they were little more than a theory — a kooky mathematical answer to a physics problem. Even astronomers at the top of their field weren’t entirely convinced they existed. Today, not only are black holes accepted science, they’re getting their pictures taken by a collection of enormous, synced-up radio dishes on Earth.

Unlike a planet or star, black holes don’t have surfaces. Instead, they have a boundary called an “event horizon,” or a point of no return. If anything swoops too close, it will fall in, never to escape the hole’s gravitational clutch.

Mashable Light Speed

The most common kind, called a stellar black hole, is thought to be the result of an enormous star dying in a supernova explosion. The star’s material then collapses onto itself, condensing into a relatively tiny area.

But how supermassive black holes, millions to billions of times more massive than the sun, form is even more elusive than typical stellar black holes. Many astrophysicists and cosmologists believe these invisible giants lurk at the center of virtually all galaxies. Recent Hubble Space Telescope observations have bolstered the theory that supermassive black holes begin in the dusty cores of starburst galaxies, where new stars are rapidly assembled, but scientists are still teasing it out.

The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy — about 15 million light-years away in the constellation Hydra — is one such starburst galaxy. It has baffled scientists for decades as they struggled fruitlessly to find signs of a black hole at its center.

Webb, a collaboration with the European and Canadian space agencies, was mainly designed to study the early universe, star formation, and distant galaxies. But its extreme sensitivity to infrared light, invisible to peoples’ eyes, gave it the power to find clues that other telescopes couldn’t, said Linda Smith, a co-author on the paper.

Infrared light can shine through dust, which often blocks other forms of light. This gives Webb an advantage in studying cloudy areas where stars are forming or giant black holes might be active.

Though the detected signals strongly suggest the presence of a black hole, the team is considering other possible sources, such as powerful shock waves moving through space or inordinately massive stars. The researchers plan to follow up their observations with other telescopes to look at the galaxy in different ways.

“Now we have fresh evidence that challenges past assumptions,” Smith said.